Four (minus one) for Friday

A group show at Anthony Gallery, Ari Norris at David Salkin and McArthur Binion and Jules Allen at Richard Gray.

Ari Norris: Just Dust @ David Salkin Creative

If we consider monumentality as a preoccupation with time that refuses to acknowledge itself as being subject to its machinations, the work in Ari Norris’s Just Dust seems to be operating on opposite terms. Instead of pleading to eternity, Norris appeals to something that actively invokes an expectation for disappearance only to stubbornly stay still. At hand is an office space cataclysm alongside four delicate wall works playing apophenic games of art-historical eye spy. The show feels like if you turn around it will be gone, and I would argue this is another gesture designed to circumvent monumental thinking. Whereas a monument requires of itself a certain feigned indifference to its viewership—eternity can have no real audience—Norris’s sculptures demonstrate tremendous fealty to any given eye.

If you aren’t a blue-chip artist exhibiting in warehouse spaces or have a team of assistants to aid in elaborate fabrication processes, the pursuit of large-scale sculpture often isn’t feasible. This simple fact makes And This is the Moment, Norris’s precarious filing cabinet tsunami, feel like a refreshing reacquaintance with the possibilities that games of scale can offer a practice. The entire show toys with trompe l'oeil, a tried and true Chicago crowd pleaser, but Norris’s sculpture nakedly reveals the kind of gimmickry inherent to the technique.

In the interest of Midwestern humility, Norris doesn’t try to make any of his materials—wood and paint for the filing cabinets, paint and resin for the wall works that mimic styrofoam—seem like something more than they are. Rather, like the radioactive green relish that blankets a hot dog, Norris prompts his wares to look less like themselves in order to express their capacities in unexpected ways. Comparisons to Chris Bradley or Tony Tasset, whose underrated Snow Sculpture for Chicago sits just down the street from 1709 W. Chicago, feel inevitable, but Norris doesn’t seem so much interested in verisimilitude as he does in sputtering on representation’s brake pad, keeping the work just short of tipping over the edge of being too much. A picaresque of utilitarian characters breaks out on the filing cabinets’ tumbling surfaces; a roll of painters tape scales the incline like a skilled alpinist; others watch the unfolding catastrophe from the summit. Pencils shoot through what ought to be steel, erasers hold on for dear life, and stray skids of blue tape and scuff marks become painterly embellishments on the sides.

As for the titular series Just Dust, four painted resin works mimic dusty, pareidolia-inducing chunks of styrofoam. Each instance appearing as if dust had settled on it just so to create the impression of four wintry paintings by Pieter Bruegel the Elder: Hunters in the Snow, The Census at Bethlehem, Winter Landscape with Skaters and a Bird Trap, as well as Adoration of the Kings in the Snow. Each painting gently rests on the surface, and it feels as if any stray breeze—or sudden gust of air should the sculpture collapse—would wipe all traces of the image from the surface. Norris has made the move to depopulate the landscapes, complicating the painting’s reproduction and proposing that maybe what is bound to last is rarely human. Styrofoam will last longer than your favorite painting, and the illusion of a looming cataclysm will induce more anxiety than the sudden clatter of metal spilling over. All is still, but wanting to go further, like the awkward silence at a funeral, just the thought of a laugh will cause the whole thing to come down. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust, as they say.

Just Dust is open. Unsure when it closes.

Isabelle Albuquerque, Mario Ayala, Ross Caliendo, Jane Dickson, Esiri Erheriene-Essi, Sharif Farrag, Theaster Gates, Sayre Gomez, Alfonso Gonzalez Jr. Lauren Halsey, Arthur Jafa, Rashid Johnson, Melissa Joseph, Friedrich Kunath, Tony Lewis, Eddie Martinez, Tony Matelli, Keith Mayerson, Tyler Mitchell, Ludovic Nkoth, Pat Phillips, Sterling Ruby, Tschabalala Self, Hajime Sorayama, Martine Syms, Cynthia Talmadge, Henry Taylor, Hank Willis Thomas, Issy Wood, Masaomi Yasunaga, Come One Come All, @ Anthony Gallery

Come One, Come All, the current, star-studded exhibition at Anthony Gallery claims that although the artists assembled are stylistically diverse (which really isn’t the case), the common thread holding their work together is a shared sensibility for provocation. While the likes of Arthur Jafa, Hajime Soriyama, and Isabelle Albuquerque (among a few others) are no strangers to stirring, transgressive, or downright trollish work, nothing here feels like it’s going to reinvent the way an audience thinks about the world, nor is it likely to spark congressional hearings over public decency anytime soon. If anything is provocative about Come One, Come All, it's that it feels as if it were curated by an algorithm; and were there to be a common thread between artists, it would be the high market valuations many of them enjoy.

This isn’t to say what is on view is necessarily bad; on the contrary, it’s mostly solid work. The crux of the issue is that I struggled to see any instance where an artwork benefits from its placement or inclusion in the exhibition at all. In this sense, Come One, Come All feels like a team stacked with top-tier talent but with a middling record because no matter how great any individual component is, nothing gels. Were there to be any exception to this, it would be the very subtle interplay between Martine Syms She’s Weird but She’s Cute, a photograph of a dingy-looking gas station in the Cayman Islands named “Hell Service Station, and Tony Matelli’s Weeds, which ruptures through the crease where floor meets wall, not unlike the flora one might expect to see popping out from pavement at many a rural gas station. At last something resembling a quiet relationship is formed: Syms’s work rescues Matelli from feeling too precious, and Matelli heightens a certain type of atmosphere present in Syms’s photograph, bringing it off the wall and into the viewer’s space.

There is way too much work crammed into the show for serendipitous interactions like this to occur beyond once or twice, and it’s doubtful that a more discerning hang would have created stronger results without taking considerable subtractive measures. Matters are made worse by the ways sculptures are given little to no room to breathe. The Albuquerque piece, for as little as I care for it, could hold a room all to itself. Similarly underserved is Arthur Jafa’s LeRage (Small), a miniaturized version of his larger cutout of the Hulk going berserk in grayscale. For the explosiveness its central figure implies, Le Rage (Small) feels stifled, backed into a corner by the works flanking it. Given a bit more breathing room, it would have the potential to do big things (see American Standard Co.’s presentation of the same from January this year).

All in all, I was left disappointed at the way a solidly promising roster of artists was handled so unambitiously. However, I would say it’s still worth going by to experience more than a few of the things on view. As always, Tony Lewis’s contribution to a group show is predictably strong. Inside Problems on a Beautiful Day features a bruisingly indeterminate bit of text that reads, “I can never enjoy in the back of my mind I always know I got go t”, which maybe is a good mantra for a critic.

As for Henry Taylor, I may not fawn over his work due to my lack of fervor in portraiture, but damn can he paint, and he makes it look so easy. Likewise, I’m normally indifferent towards Tschabalala Self, but I found a smoldering elegance in Self’s Muse 3 Centered as well as a deft treatment of how she employs her fabric and makes use of the space on the canvas. On the other hand, Orgy for Ten People in One Body: One, Albuquerque’s headless bronze nude playing a saxophone from its nethers elicits a chuckle and thoughts of American Pie’s famous band camp line, but it lacks the more venomous tenor reached by counterparts from the same body of work.

While I was looking forward to seeing one of Soriyama’s sculptures in person, my ability to enjoy it was stunted by the presence of a gallery assistant who conspicuously shadowed my every move. It feels corny to act like a medium-sized gallery requires the same security precautions as the Art Institute, and I might have spent more time in the show if I weren’t so irritated by it. If you hate being looked at as much as I do (perhaps a result of years of being gawked at for my height), skip it, but if your threshold for an audience is higher than mine, it’s more than worth the visit.

Come One, Come All is on view until May 11.

McArthur Binion & Jules Allen Me and You @ GRAY

Richard Gray seems to think Jules Allen and McArthur Binion’s friendship is enough to justify their insistence on this being a duo outing, but in reality, Me and You feels more like two intentionally adjoining solo exhibitions. Allen and Binion’s pairing is the result of a fairly unobjectionable proposition: they are old friends, and both are masterful formalists; ergo, they fit together. Keeping their work largely separate by a temporary wall, however, doesn’t exactly lend itself to developing a strong dialogue now, does it? Beyond petty gripes over how the show attempts to position the work, I can say that it’s worth seeing.

I have little to say about Binion’s work that hasn’t been said by persons more intelligent than myself. He is a consummate rules-based painter, and his good sense for limits is what grants him space to improvise within structure. It’s also what allows the structure to feel so haptic; nothing is particularly square, but there remains an overarching sense of order still bound to the artist’s hand. There is a near-juridical system of image-making applied by the oil sticks he has made use of for the last five decades. The color choices for the show avoid being too chromatic. Things are kept at a smolder: deep purples and a slew of earth tones form the most common palettes; a fecund green occupies a few of the more melodically inclined tableaux.

Beneath Binion’s latticework, a selection of images can be found ranging from personal archives to musical scores and historical atrocities. There is no hierarchy to delineate one image’s import from the next; they sometimes share a surface or dominate another entirely as they repeat. All are part and parcel of what Binion terms the “under conscious.'” But the “under conscious” is not to be confused with the subconscious. Whereas the latter deals with wills and desires, Binion’s under conscious is more of an infrastructure for selfhood, one that coolly ebbs on the threshold of perception. Binion amplifies this phenomenon by using scrims of ink washes to bury selections of scores, personal administrative documents (birth certificates and address books), and a jarringly abstracted close-up of a lynching from 1930. It packs a punch, but its impact is determined by repetition. Binion ensures viewers pay the price of admission that comes with witnessing his self-reflection, because if that feels a bit too much to deal with, maybe you have little business being around for the rest.

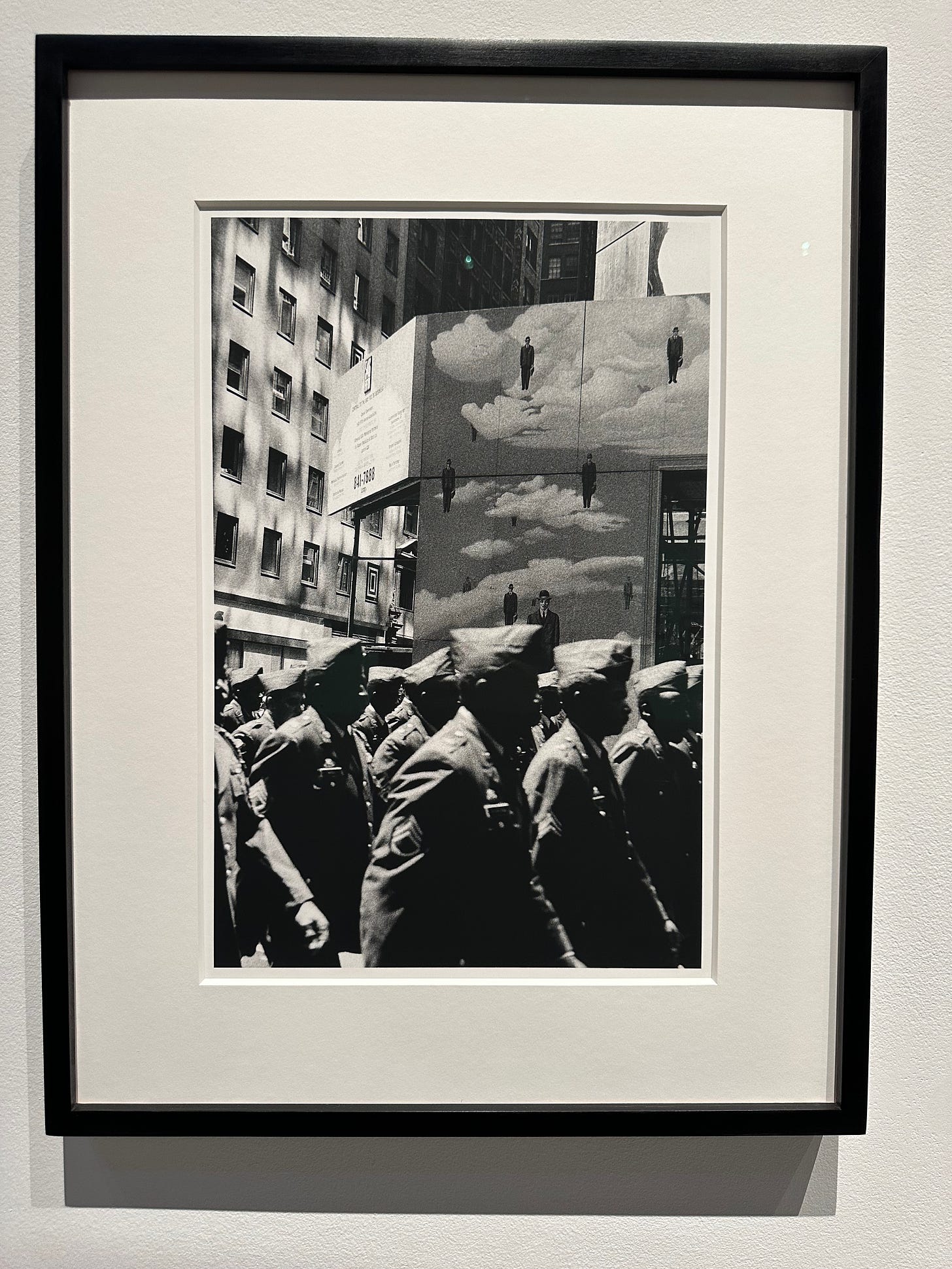

In the rear half of the Gray warehouse, just over the wall, Jules Allen’s photographic works present a comprehensive set of images synthesizing a documentarian’s concerns with the eye of an all-American formalist. Allen has a knack for contrast and tonality that his counterpart also demonstrates, and perhaps passing through Binion’s half of the exhibition first will calibrate viewers’ eyes not to look at Allen’s photographs too literally. Shadow is used expertly as a way to build space and cut shapes out from bodies, fabric, and architecture. While Allen might seem to have a preternatural gift for being in the right place at the right time, I would argue that the placement of Allen’s camera never feels opportunistic; instead, it is vividly active in instigating opportunities to create an image: a sea of soldiers whose faces are veiled out by shadows walk below a billboard featuring a Golconde-like advertisement; an assembly of women shading themselves from the sun with their parasols creates a geometric cacophony. Of course, nominally being a “street photographer,” Allen’s portion of the show is more straightforward and leaves less to interpretation but perhaps prompts more of an overall conversation around composition, which, come to think of it, might be the real meeting point between Allen and Binion.

Me and You is on view until May 31.

Went to the Anthony Gallery exhibition and had the gallery attendant follow me as well - felt super uncomfortable and pressured to view the works quickly thus limiting my experience.