Three for Thursday

Leonardo Kaplan @ MICKEY, Group Exhibition @ M.LeBlanc and Autumn Ramsey @ Soccer Club Club

Good afternoon, I greatly enjoyed my two-week sabbatical from writing, but am back with another edition of my alliterative weekly reviews. Once Summer is in full swing I will probably be publishing a bit less because as we know, art gets pretty boring between June and August, and I prefer to spend my summers slamming two-dollar beers in the park as opposed to slinging ten-dollar words from my attic. I’m also hoping to shift gears and strike a stronger balance between exhibition reviews and more long-form, polemically oriented works that will probably come out on a monthly basis if I can manage. Anyways, here is this weeks slate of reviews, all pretty positive, the hate fest is next week:

Leonardo Kaplan: Chlorine Luck @ MICKEY

Chlorine Luck suggests a fortuitousness bleached of its charm by sanitary convention, a bitter taste to something that should have been felicitous. If there is a better analogy for living long enough to become a “productive member of society,” I’m waiting to hear it. Everywhere you look, people seem to be making work about youth—or at least the outré cultural pallbearers that signify it—because the past is easy; it is familiar; it is a temporality we can retroactively claim mastery over despite our helplessness in the present moment.

Most artworks that attempt to capitalize on the niche yearnings of yesteryear can be written off as either navel-gazing revisionism or Y2K LARP masquerading as introspection. On the other hand, there is Leonardo Kaplan’s brand of slacker-branded spiral-bound notebook nostalgia and shit-head bathroom-stall style tags, which succeed at a high level because he doesn’t over imbue his references with more sanctity than they are owed.

Although a diaphanous explosion of color sets the tone for most of the exhibition's works, any sense of exuberance is firmly grounded by way of tickets, utility bills, and to-do lists littering their respective tableau. Against their airbrushed backgrounds, Kaplan’s use of image transfer is ultimately the most crucial material choice. The dissolute images that populate his canvases are on the edge of not being there at all; they are holdovers from another thing and another time, adhering as a copy of a copy.

Looking like they’re already dissolving, the photo-transfers feel like the temporary tattoo your cousin gave you in the summer of ‘03. They even carry the suppressed giggling impishness of believing someone's mom would think it was real and flip her lid. I cannot begrudge Kaplan’s indulgence in the obvious and obscure(d) cultural holdovers of the Y2K era because he doesn’t use them as crutches. Instead, they are obstacles that the paintings (and by extension himself) must navigate as formal and semiotic agents within the broader scope of painting as a meaning-making system in an increasingly oedipalized and bland cultural milieu.

Mortality and its discontents prevail throughout much of the work. One of the more minimally maximalist instances in the exhibition is titled The End of Heaven is not Hell, which burns away a Constable-esque cloudscape for the ice-dyed limbo behind. Snow in Spring invokes Charlie B. Barkin, the charmingly unscrupulous hound from Don Bluth’s All Dogs Go To Heaven (1989). Similarly rendered in ballpoint pen is Cow & Chicken’s infamous “Red Guy” (the Devil), hidden amidst a veritable glossolalia of references blooming and receding from clarity in Please Hold. Both characters are drawn directly onto the surface rather than transferred, stemming more from memory than a larger repository of ready-made images to adhere to and peel off the picture plane.

Likewise, Looney Tunes characters sprout up here and there, especially Wile-E Coyote, whose hapless antics don’t seem as farfetched as they used to considering the lengths most people will and must go to to put a meal on the table. Let the World Be Itself features a book entitled Corruption: A Short History from the ubiquitous academic publisher Routledge, which says all it needs to with just the volume’s title but drives its point further home with Venom from the Spider-Man comics greedily wrapping his tongue around the base of a cheap ceramic tsotchke.

In MICKEY’s smaller gallery, Kaplan has made three large image transfers of the backsides of CDs. The trio of works occupies the entire surface of their respective canvases and lacks the dissolution prevalent across many of their cohort in the adjacent room. Instead, they feel like inaccessible containers of affects, knowable only through their titles (Cloudy Day Mix, Breakup Mix, and Shower Mix) and the anxious contents of their reflective surfaces. Breakup Mix proves itself to be appropriately languishing, down to the minute of the day (8:39 PM) scratched into the surface of the disc.

Chlorine Luck has the good sense to make everything feel intentional in a way that retains an overwhelming discord native to both memory and the internet, which are, at this point, functionally the same thing. Life can be callously straightforward: tomorrow you will wake up, and you will deal with all of your shit again. Maybe this is bleak, but it's obvious that Kaplan is searching for a language inclusive of yesterday but addressing today. If the paintings on view at MICKEY are evident of his thoughts on the matter, I doubt his search is without hope.

Chlorine Luck is on view through June 08.

Lauren Burns-Coady, Andy Hope 1930, Sergej Jensen, Arnold J. Kemp, Bjarne Melgaard, Matthew Pang, Nicole-Antonia Spagnola, Cameron Spratley @ M.Leblanc (co-curated by Eric Schmid)

The exhibition’s lineup is a familiar mix of regulars from both Eric Schmid and Marc LeBlanc’s respective rolodexes, and while audiences may be left questioning the goals of the collaboration, the exhibition is not without its fair share of things worth seeing. On their own, this group of artists is all talented and has very diverse CVs, but of course the standout was always going to be Bjarne Melgaard, if for novelty’s sake alone. That this is his first time showing in Chicago is a shameful testament to how risk-averse and provincial the city has been—especially at the institutional level—for the past twenty years.

The Lion Sluts drawings find Melgaard in classic form, returning to the motif of the big cat as a stand-in for himself in thick scumbled line work on paper featuring long-winded, semi-legible captions near their wild-eyed, anthropomorphic subject. As opposed to the put-upon misery of his drugged-out Pink Panthers, the Lion Sluts illustrations are less caustically confessional and more earnest, circumspect even. Interspersed between the drawings are photographs of Melgaard engaged in a bevy of graphic sex acts. The disjunction between drawn image and borderline hardcore pornography heightens the drawings’ power, because in spite of just how raw the photos are, the sentiments expressed in the drawings still feel more naked. “I don’t manage to draw this magic in my bad drawings,” reads Lion Sluts IV, a love letter to Melgaard’s husband, Patrice.

Nearby, the intensity is maintained with Arnold J. Kemp’s Spanking Bench (2016). Which includes an attractively fabricated version of its namesake, along with two silver-painted Fred Flintstone masks—presumably for the absent parties suggested by the bench—along with a group of four books. All in all it works: discipline, performance, queerness, history, and the dichotomies of male aggression and play are all on view, reinforcing my belief that Kemp is one of the best and most criminally underappreciated artists of his generation. The apparent laziness of Spanking Bench puts Kemp’s formal chops on full display. It’s completely apparent that he knows exactly what objects can simultaneously destabilize and enrich the existence of others with the most back-handed ease.

As for Cameron Spratley, whose painting hangs nearby, it’d be easy to talk about the effects that image boards and the visual culture of hardcore punk and horror rap have had on his practice, but that’s been done. The conversation I want to see develop is for someone to dovetail all of the obvious contemporary referents into a broader revitalization and appropriation of traditional still-life painting categories, which Spratley does well without employing ham-fisted irony. Sergej Jensen’s Men With Hats feels like a crowd of voyeurs watching the rest of the work unfold from the back corner, and Andy Hope 1930's Runaway Room paintings have the opposite effect and seem like a quiet, albeit humorous, moment to turn down the sensory overload.

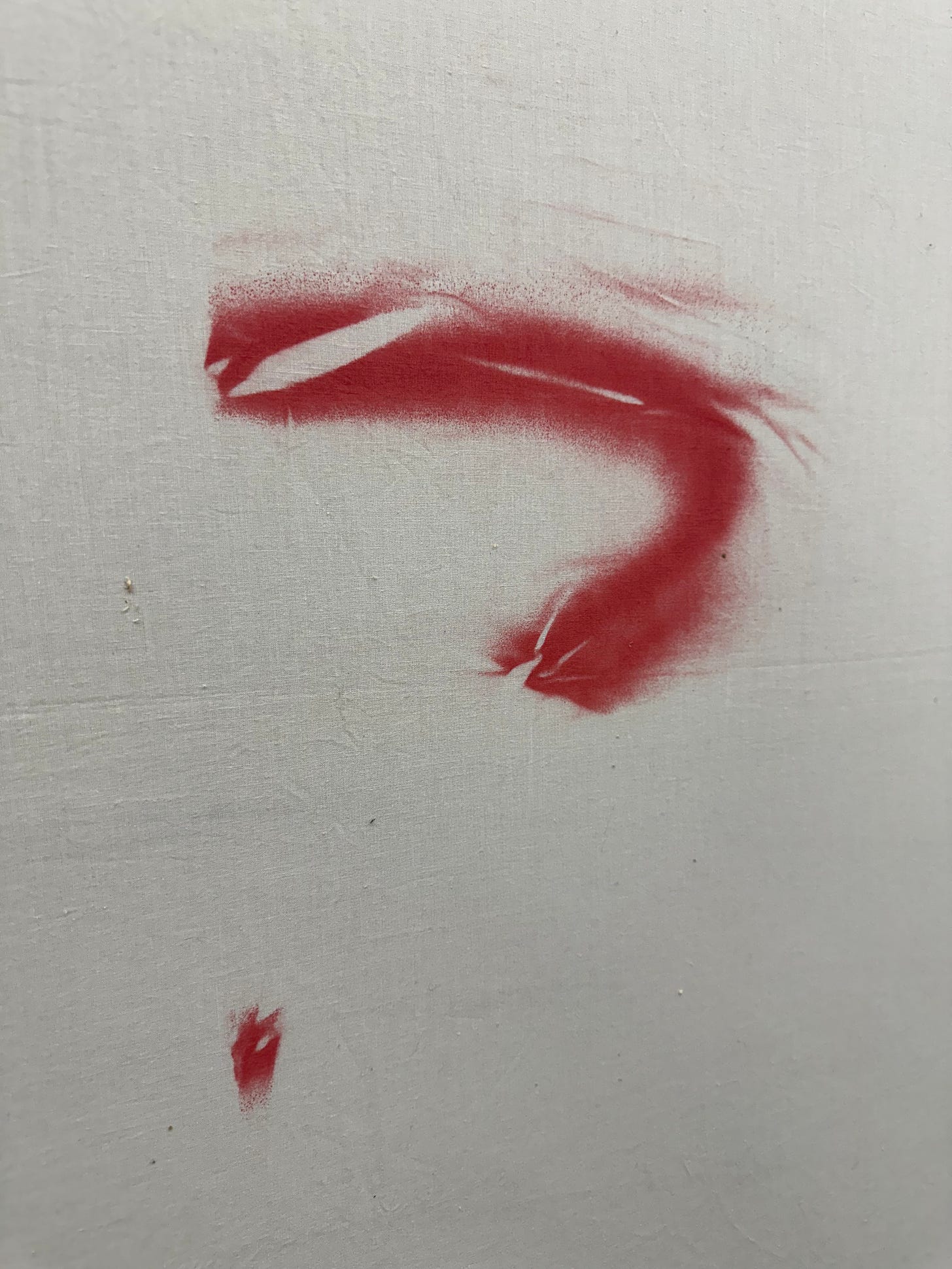

In the back half of the gallery, Lauren Burns Coady’s BB&B BB7 (Akulina Cream), a duvet cover hastily shot with bright red spray enamel paint towards the top, affects a completely disenchanted air of analytic cool and know-how. The material of the duvet is immediately apparent, and the high chemical red against the cheap wrinkled surface feels insolent and alluring all at once. Matthew Pang’s two drawings, Kornelija Venom 3 & 4, feel like topographical maps concealing alien symbiotes and frenetic stalker-esque notebook drawings of the object of one’s affection.

By the end of my visit, how things gelled really wasn’t much of a concern. Things stood alone rather well, and considering many of these artists don’t get shown with much regularity (if at all) in Chicago, I recommend you get there and enjoy the work before it closes..

Lauren Burns-Coady, Andy Hope 1930, Sergej Jensen, Arnold J. Kemp, Bjarne Melgaard, Matthew Pang, Nicole-Antonia Spagnola, Cameron Spratley is on view until May 24

Autumn Ramsey @ Soccer Club Club

Soccer Club Club is my favorite place to see art in Chicago. Simple as. It isn’t particularly self-congratulatory despite being one of the most consistent spots around; it’s low-key and is covered in chintzy wooden walls and floor-to-ceiling mirrors that force whatever is on view to sink or swim. It’s a convivially endearing and enduring space in an art world where most exhibition venues and the content promoted within feel so unintelligent, sexless, and devoid of life that they could easily be confused for an unfinished Sweet Green.

Currently on view is a self-titled presentation from Chicago’s own Autumn Ramsey, which amounts to more-or-less an informal survey of the last fifteen years of the artist’s practice. Ramsey, who has been and remains one of Chicago’s best painters, is also one of its most inconspicuous. Despite her obvious chops, Ramsey hasn’t shown in the city she calls home in nearly a decade, opting instead to exhibit prolifically in France, as well as New York and L.A.

In addition to works dating back to 2009, Autumn Ramsey mainly expands on the artist’s repertoire of garden paintings from recent exhibitions at her galleries, Crèvecœur and Paul Soto. Newer works don’t necessarily imply or overvalue themselves in comparison to their forebears, and older ones aren’t so much re-contextualized as they are lucidly clarified within the broader formal and conceptual program of Ramsey’s oeuvre.

Indulging in a bit of metaphor, the garden acts as a figurative locale for the cultivation of a practice and space for discernment. Ramsey’s chosen forms feel coequal to their referents insofar as they wield the properties of the painted surface in a manner that completely consumes the eye and mind. They are decadent, easy to get drunk on, but also maintain a predatory, inhuman edge inherent in all things that are truly beautiful. Ramsey’s facture is masterful, and much of her recent work finds her programmatically modulating the shape, density, and hues of foliage without getting too formulaic. There is a constant shift in where light is coming from, drawing the geometry of the gardens into a seemingly non-Euclidean dimension and highlighting Ramsey’s knack for scintillating atmospherics. Oil is applied at times like mortar, and at others it’s practically whispered on, barely present, gossamer thin.

In Ramsey’s pictorial vernacular, flora, fauna, and the figure become an allegory for femininity and the act of painting itself. Historically, nature and womanhood were things to be molded, contained, managed, and gazed upon as passive reflectors of beauty within a prescribed universal order. Conversely, painting functioned as a means to deduce and extract higher virtues out of the natural world’s disarray, distilling its objects into a mastered, sensible form. But where flowers grow, birds frolic, maidens preen, and wild-eyed hogs run amok beneath the pale moonlight, Ramsey suggests a corporeality that cannot be managed or tamed. It isn’t so much that the paintings are refutations of an extractive, chauvinistic gaze but rather are demonstrative of an unflappable indifference towards being rationalized as such.

The exhibition’s hang is sparse but smart. Along the backmost wall, across from the bar, seven paintings are lined up edge-to-edge, forming an improbable frieze of images bookended by recent garden paintings. Included in their midst is a glowering, spectrally pale, made-up face with heavy eye shadow (Mary Kay, 2017), which is reminiscent of Lee Godie’s painted ladies. Additionally, the aforementioned boar sprints ahead, indomitable as Delacroix’s stags and wild as the one slain by Hercules (Boar, 2017). The “frieze” also contains the show’s oldest painting, a small work from 2009, Looking for Jane, which depicts a seated female nude with vague, indeterminate features reminiscent of a homunculus. The progression from the gardens, through the figures and boar, operates like a Dionysian reverie of difference as such or difference becoming different within each painting. This sense of boundless, inhuman bliss isn’t isolated to any one specific instance but is actually the vibe of Ramsey’s whole practice.

Amongst other works worth noting are Branch (2013), where a dove melds seamlessly with the delicate pastel ground that gives rise to the bird, and Wedding Portrait (2011), a humorous and inventive approach where Ramsey has painted directly over a framed antique photograph, selectively revealing and incorporating the contents below into a pastiche of baroque, academic romance. The works of Autumn Ramsey decisively invert painting’s program as an articulative tool within the enlightenment project by attuning its techniques towards the affective and sensitive rather than the empirical. The images retain an analytical edge, but one that feels spontaneous rather than practiced, as if, by experience of being observed for centuries, Ramsey’s well-tread subjects now know how to cast an eye back at us.

Autumn Ramsey runs at Soccer Club Club until May 31. You shouldn’t miss this one.