Judith Dean, Ella Rose Flood, Sophie Friedman-Pappas, Nöle Giulini, Maureen Gruben, Paul Levack, Eli Ping, Michelle Uckotter, Olivia van Kuiken @ Bodenrader

What I want most from any exhibition, but especially a gallery’s first, is to see some kind of claim as to what art matters to that space. Unfortunately, this impetus is rarely ever attended to, but Bodenrader’s opening salvo seems to meet the task head on. The exhibition forgoes potentially chintzy shit such as a press release or title, cutting straight to the point with a well organized group of artists; who across varying ages, histories and material sensibilities cohere in an exhibition that oscillates between delicacy and a certain inhuman vitalism.

Restraint is always an important, yet seemingly difficult thing to exercise when organizing an exhibition. In a group setting with eight people, having only one work per-artist feels like a good move. It allows each piece to maximize its effectiveness in conjunction with its peers and avoids watering the show down with too much of one energy. This opens up room for artists to be placed in a logical proximity to those whom they share the most affinity, while maintaining a fluid conversation through and with space.

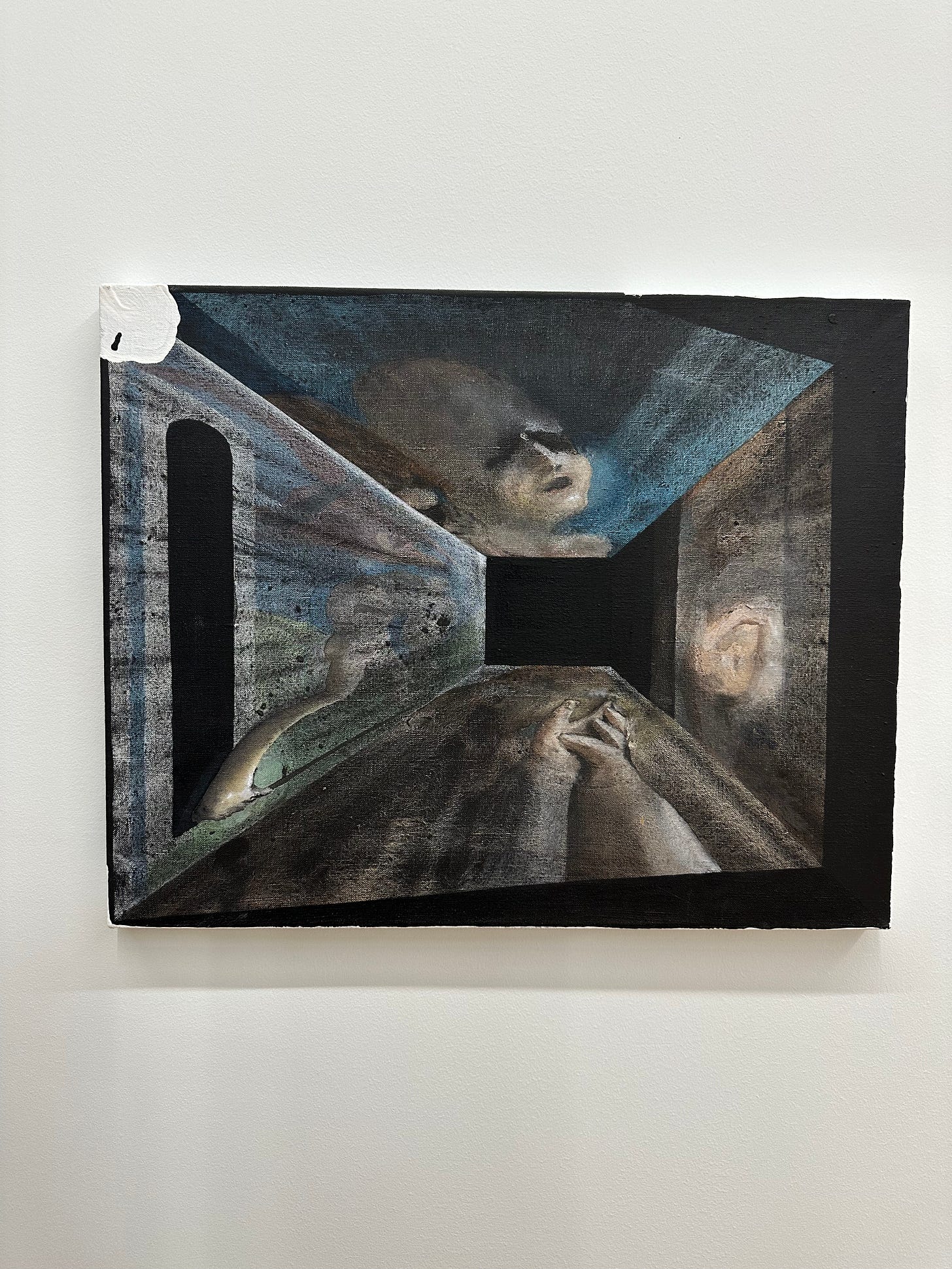

Paintings by Judith Dean and Michelle Uckotter flank the entrance near the stairs, allowing each to communicate with one another as well as the egress into the gallery in general. Both painters share kindredly tactile surfaces – albeit by different means – and a serial engagement with specific architectural forms that build morose and forebodingly anxious tableaus. Uckotter’s faceless gray jeunes filles often find themselves in proximity to an entryway or stairwell, while Dean paints a long warped hallway where languishing figures are projected on the walls and ceiling. There is a moment in Deans A+E, that I found particularly resonant: a white glob of paint that interrupts the top left corner. It breaks the illusion of an already wonky picture plane, but somehow seems to extend the image’s psychic anguish more into the audience’s space in addition to roping the work into conversation with Eli Ping’s gooey hydrocal lacuna sharing the same wall.

Placing Ella Rose Flood’s Bug funeral IBGuard blister package – depicting insects interred in a medicine package’s plastic pockets – adjacent to Paul Levack’s optically challenging photo work feels like a natural pairing. I’ve always felt Flood’s practice holds a stronger conversation with photography than it does with most other paintings in how it negotiates with the selection and distribution of images, but also in how her works’ matte surfaces always seem to produce their own illumination from the back, much akin to a screen.

Holding the room’s center and backmost corner are the exhibition’s linchpins – Maureen Gruben’s Fresh Artifacts (2017), and Nöle Giulini’s Meyerkappe (2008). Together, they set the show’s pitch like a tuning fork, and while their most interesting conversations are had with each other, they also undergird a conceptual framework with just about everything else on view.

Resting solemnly in the corner, Giulini’s contribution looks like a corpuscular medieval cowl meant to signify some kind of ghastly avian. It's made up of dried Meyer lemons, frankincense and myrrh resin, while the crags between dusty fleshy rinds pop with the blood red threads that hold it together. Its imposing shape, familiar-yet-alien material and conspicuous lacunae seem to still be brimming with some kind of life that objects worn in ritual performances often have. This is not so different from how Gruben’s series of three hanging resin sculptures operate. Fresh Artifacts, feel like animal pelts or new carcasses hung out to dry post-slaughter. In light of their formal resonance, the title seems to caustically chafe at the way in which work by Indigenous artists is often promptly metabolized by a colonial imaginary, making anthropology out of even the most cosmopolitan of practices. As their forms dangle about, you half expect something to drip out or off of them while they hang, but instead, they gently sway playing the part of warped and gelatinous windows onto the other works nearby.

Bodenrader, like its Chicago predecessors Jargon and HG, seems to already have a penchant towards work bearing a hallmark or undertone of violence, which can be glaringly apparent or softly implied – sometimes from different vantage points of the same work. However, intimations of paranoia, loss and repression don’t weigh down the mood of the show. On the contrary, they build cohesion amongst subjects and perhaps even offer something of a cogent expression into the ways contemporary practices must often navigate the specter of imminent collapse without resorting to pearl clutching or irony-poisoned doomerism. In much of what is on view, it feels as if the disaster has already passed anyway, and the work, much like the gallery itself, is a forward thinking iteration of something from the past ready to rise out of the ashes.

Bodenrader is open 11 – 5, Wednesday – Saturday. The exhibition closes November 25.