Isabelle Frances McGuire, Ryan Nault, Liz Vitlin, Ellis & Parker von Sternberg: Speedrunners @ Twelve Ten

“If you want to make it, you have to play the game.” We all have been guilty of saying or thinking this. The freedom of play that is presupposed by art in theory is often inversely proportional to the freedom (time and money) that would allow one to successfully play in the gamified sphere of contemporary art in practice. Speedrunners, the first show at Edgewater’s Twelve Ten, features Chicago mainstays Isabelle Frances McGuire, Ryan Nault, and Liz Vitlin alongside New York’s Ellis and Parker von Sternberg in an exhibition that highlights certain ways of making that maliciously comply to the de facto rules we all follow by our participation in art and life.

Ryan Nault’s paintings feel like the purgatorial screensavers that appear between levels, way stations that function as a ground for interactions between social classes. Nault’s blearly renderings of luxury shopping spaces, boutique shelves, and penthouse views imply something both close enough to capture but still distant enough to feel like a mirage. The natural shimmer imbued by the gouache in Nault’s hand gives the impression of things and places as if they were viewed through the glass and water of a fish tank. Who sits on either side of the glazing remains ambiguous.

Artists are not unlike many in-game protagonists. They oscillate back and forth in status from being the help to being the hero. Often the same people who will ignore your existence when you're delivering hitty painting to their apartment will be the same ones asking for a discount on your own work the next Friday. The character of the artist is duplicitous by necessity, and in Nault’s case this takes the form of selling the collector class alienated depictions of their own milieus. The precarious and unclear position that working artists assume in many social dynamics recalls advice sent by King Leopold I to Queen Victoria that one must be cautious with artists for the fact “they are acquainted with all classes of society, and for that very reason, dangerous.”

In the back, Isabelle Frances McGuire’s dioramic portrait, Napoleon's Chest, What Pipeline, reduces its historical namesake to the trappings of costume—imperial blue fabric, metals of honor, and hella tassels—which are immediately recognizable stand-ins for his character. The shiny white foamboard and the pins clearly holding it together make it feel like a storyboard or an elementary school presentation done with only the most cursory look at the portrait done by Jaques Louis David. The only anachronism is that McGuire has placed a lightbulb front and center, the LED filament of which forms a heart. Deracinated from every detail save for style, Napoleon—like most historical figures resuscitated by the popular consciousness—becomes cute. No longer a petty reactionary that reinstituted slavery in the East Indies, Napoleon is instead a haphazardly constructed NPC among many, a “wee wittle man wid a big dweam” <UwU>.

Meanwhile, Ellis and Parker von Sternberg have gotten busy playing games with the gallery’s infrastructure. The back door’s white, rectangular security bar (Security Bar, 2023) has been placed on view parallel to Twelve Ten proprietor Joshua Johnson’s own Xbox console (Xbox Series S, 2023). The Xbox functions as a signpost for a kind of mutually assured destruction as it relates to the removal of the security bar. Rarely do gallerists risk anything of personal value by placing the fruits of someone else's labor in their space. However, should anything happen, an item belonging to Johnson is also vulnerable—and in the case of a video game console—more likely to be in danger of vanishing than the art. The gesture insists on weaving the artists’ own fate with the gallery’s, raising the stakes for all parties and helping to delimit the field of play within Twelve Ten. After all, outside a certain context, art is fecklessly unable to communicate its social value when competing against more immediate forms of entertainment.

As for the series of photos that hang above the Xbox and remain wrapped in plastic — I quite like the images, which are reminiscent of looking for dead bodies on Google Earth. The plastic probably makes it feel more sinister beneath the wrapping than they would otherwise. Unfortunately, I have a gnawing feeling they could have been left out of the exhibition, maybe due to how similar they feel to Jef Geys’s Bubble Paintings. I get it’s more so about the authority of the framer making a set of decisions as to how a work is ultimately displayed (and as a framer myself, I appreciate the nod), but that particular gesture still feels anonymized by how cryptically seductive the photos themselves are.

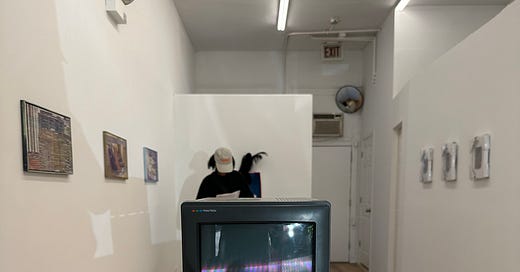

Liz Vitlin’s video and sound works, MOV02225.MPG [October 29, 2005], and Grandparent Bio Ch. 4 Side B.wav [2005] feel inescapable in Twelve Ten’s modestly sized Thorndale Ave. storefront. As part of the first generation of artists who grew up with the technological access to archive one’s entire life, Vitlin mines old homework assignments, video, images, and sound from her childhood, which comprise the majority of her artistic practice. MOV02225.MPG [October 29, 2005] makes use of a small CRT that plays a grainy 40-or-so-second loop of a young woman laughing, pantomiming, and rolling on the floor. On top of the video is a 20-minute recording of FM radio channel hopping. Top 40 hits circa the mid-aughts phase in and out, some sticking around longer than the others. It can’t be helped but to move about the gallery, tuning in and out, knowing the words here and there. It’s easy to be caught muttering along or cracking a smile when particularly memorable songs make an appearance. This will differ from viewer to viewer.

Admittedly, I’ve had a hard time with selective aspects of Vitlin’s practice in the past, but her consistent treatment of video and sound continues to keep me happily engaged. Maybe it’s the way such a brief video repeats itself so rapidly it practically breaks into identical fragments. More an artifact than a memory, more mythologizing than nostalgic—these aren’t so much videos from Vitlin’s childhood as they are videos from Vitlin’s Childhood-Arc.

The artists in Speedrunners benefit not only from the exhibition’s conceit but also from their proximity to each other’s work. After spending some time on it, it feels that the exhibition has traced two viable paths for play. While Nault and the von Sternbergs actively engage in a sort of gameplay that makes explicit reference to the nebulous limits of contemporary art’s gamification, McGuire and Vitlin proffer what remains to me an urgent question for a winner-takes-all art world where everyone is an NPC until told otherwise. To very loosely paraphrase Assassin’s Creed Syndicate character and prior muse of McGuire’s, Karl Marx — if “all that is solid melts into content,” then does it follow that “history repeats itself first as tragedy, then as lore”?

Speedrunners at Twelve Ten features work by Isabelle Frances McGuire, Ryan Nault, Liz Vitlin, and Ellis & Parker von Sternberg until November 11.